30. sierpnia 2021 zakończyła się pierwsza oficjalna zbiórka organizowana przez naszą fundację na rzecz Malaria Consortium (MC) – organizacji zajmującej się zapobieganiem, kontrolowaniem, leczeniem i eliminowaniem malarii oraz innych chorób zakaźnych w Afryce i w Azji. W 2020 roku prowadząca ewaluację inicjatyw dobroczynnych organizacja GiveWell uznała Malaria Consortium za najskuteczniejszą organizację dobroczynną na świecie.

Według niektórych estymacji komary odpowiadają za śmierć niemal połowy populacji wszystkich ludzi, którzy kiedykolwiek się urodzili. Jednego dnia zabijają one więcej osób, niż rekiny przez ostatnich 100 lat. W krajach ubogich przenoszona przez komary malaria to jedna z najczęstszych przyczyn zgonu. Co 2 minuty umiera z tego powodu jedno dziecko poniżej 5 roku życia.

Malaria to choroba pasożytnicza, którą powoduje głównie ukąszenie zakażonej samicy widliszka – komara z rodzaju Anopheles. Do większości zgonów dochodzi w krajach Afryki Subsaharyjskiej, takich jak Nigeria czy Burkina Faso. Objawy obejmują anemię, gorączkę i drgawki, problemy z oddychaniem, skrajne osłabienie, hipoglikemię, zapaść krążeniową, a czasem niewydolność nerek i śpiączkę. Nawet wśród tych zarażonych, którym udaje się dotrzeć do szpitala, około 1/5 wciąż umiera. Oprócz dzieci, szczególnie narażone na zachorowanie są także kobiety w ciąży.

Oprócz wywierania niszczącego wpływu na rodziny i społeczności, malaria oddziałuje także na gospodarkę i społeczeństwo, m.in. utrudniając edukację młodych ludzi. Ta szeroko rozpowszechniona choroba jest zarówno przyczyną, jak i skutkiem ubóstwa. Należy ją zatem kontrolować, by gospodarki krajów przez nią dotkniętych mogły się rozwijać i wzrastać.

Jeden z programów realizowanych przez Malaria Consortium: Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (Sezonowa Chemoprewencja Malarii – SMC) zapewnia dzieciom w wieku od 3 miesięcy do 5 roku życia ochronę przed malarią w okresie wysokiej transmisji tej choroby. W ramach programu dzieci otrzymują w pełni bezpieczny lek, który zapobiega do 75% przypadków zachorowań. Celem jest ograniczenie zachorowań na obszarze położonym wzdłuż południowych obrzeży Sahary. W samym 2020 roku programem SMC zostało objętych 12 milionów dzieci.

Datek w wysokości zaledwie 7 dolarów (około 28 złotych) zapewnia ochronę jednemu dziecku w sezonie zachorowań na malarię. Potencjał na dalszą poprawę sytuacji jest bardzo duży. Obecnie niedobór funduszy sprawia bowiem, że ponad 14 milionów dzieci w Sahelu nadal czeka na objęcie ochroną w ramach programu SMC.

Podczas naszej zbiórki zebraliśmy prawie 6 000 zł, co daje prawie 1,5 tys. dolarów. Oznacza to, że dzięki tej zbiórce około 215 dzieci zostanie objętych programem sezonowej chemoprewencji malarii. A wszystko dzięki wam – darczyńcom!

Niedawno mieliśmy także ogromną przyjemność gościć Christiana Rassi, który w imieniu Malaria Consortium opowiedział nam o walce z malarią i programie chemoprewencji w krajach afrykańskich. Nagranie tego wirtualnego spotkania możecie obejrzeć na naszym oficjalnym kanale YT. Jest to najnowszy z webinarów zorganizowanych przez Efektywny Altruizm Polska. W przeszłości gościliśmy już między innymi profesora Petera Singera oraz Orestesa Kowalskiego.

Dla czytelników preferujących słowo pisane zamieszczamy poniżej zapis prelekcji Christiana w oryginalnym języku angielskim. W drugiej części artykułu poznacie odpowiedzi naszego gościa na pytania zadawane przez słuchaczy. Zapraszamy do lektury!

***

My name is Christian. I’m the director of Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) program and I’m really grateful that you’ve given me the opportunity to be here today and to talk about Malaria Consortium’s work. Specifically – to talk about our seasonal malaria chemoprevention program, which is one of the GiveWell’s recommended top charities, of course.

Over the next 15-20 minutes or so, what I’d like to do is just give you a brief overview of what seasonal malaria chemoprevention is and how Malaria Consortium supports the distribution of SMC medicines to millions of children across Africa every year. And then, towards the end, I want to give you a very brief glimpse of what the future of SMC might hold. To do this, and to set the scene, I’m afraid I’ll have to start with some rather sobering facts.

The girl you can see in this picture has severe malaria, which means that she will have a very, very high temperature. She will probably be drifting in and out of consciousness and she will be generally very, very unwell. Unless she receives appropriate medical care, her chances of survival are really low. Unfortunately, that’s a picture we still see very commonly in many parts of the world because malaria remains a leading cause of illness and of death around the world.

According to the World Health Organization, there were round about 230 million cases of malaria in 2019 in 87 countries and more than 400 000 people died from malaria. Two things I want to point out about who bears the greatest share of the burden of malaria worldwide: about two thirds of all the malaria deaths were among children under five and Africa in general accounts for the vast majority of all malaria cases and deaths – over 90%.

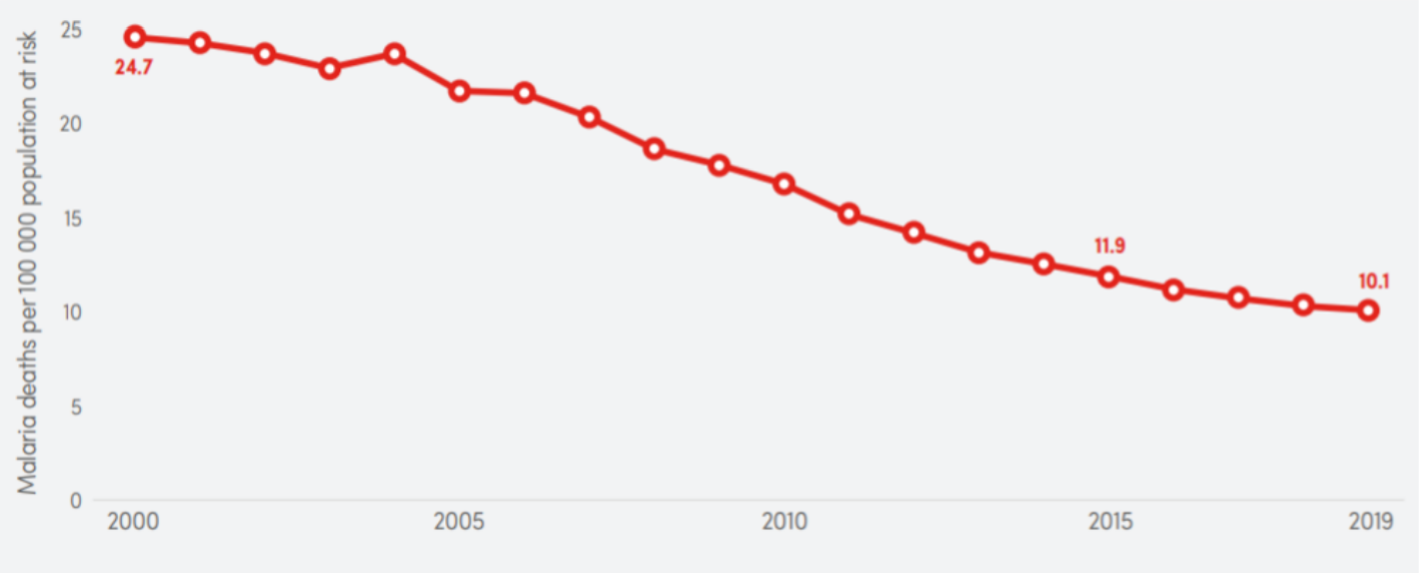

It’s not all doom and gloom yet. It’s important to recognize that a lot of progress has been made in the fight against malaria, especially since the turn of the millennium. Let’s just look at one indicator that we often track to give us an idea of how we’re progressing – it’s called the global mortality incidence rate. Essentially, that’s the annual number of malaria deaths per 100 000 people at risk of malaria.

Source: WHO World Malaria Report 2020.

If you look at this graph, you can see that in the year 2000 that was round about 25 – and the number has fallen to round about 10 in 2019. That’s really been made possible by the wide scale deployment of effective malaria prevention and control tools – you’ll probably be familiar with bed nets, you may be familiar with indoor residual spraying. Prompt access to good diagnosis and effective treatment of malaria has also played an important role. The World Health Organization estimates that between the year 2000 and the year 2019 round about 1.5 billion cases of malaria have been averted and round about 7.6 million lives have been saved since the year 2000.

That’s really good news, right? However, it’s also true to say that we’ve seen a bit of a stagnation in the malaria trends over the last five years or so. If you look at that mortality rate graph again, you’ll see that not much has changed since, say, 2015. The curve has really flattened over the last couple of years and the same would be true if we looked at many of the other common malaria indicators.

The question, of course, is what needs to be done? The answer to accelerating progress is that we really need a mix of many different responses. For example, we’re hoping for innovations such as malaria vaccines to become available at some point in the future. But in the short and in the medium term, one of the most important strategies is to better utilize the tools that we already have. In other words – we need to optimize those tools and we need to try and close the remaining access gaps. One of those tools is seasonal malaria chemoprevention and that’s the intervention I want to focus on for the remainder of my talk.

As the name suggests, seasonal malaria chemoprevention – or SMC in short – is specifically targeting areas where malaria transmission is seasonal. That’s the case in areas where there is a long, dry season with very little or sometimes no rain for much of the year.

During the dry season, there are very few mosquitoes around, because they need stagnant water to breed. If there’s no mosquitoes, there’s no malaria, so the malaria rates are really low for most of the year.

But then the rainy season starts – and the mosquitoes start to multiply. People get bitten more often and the malaria cases will just shoot up – and they will remain high for the duration of the rainy season. At the end of the malaria season, the mosquitoes would disappear again after a couple of months and the malaria rates will come down again. That’s really a pattern that we see across much of the Sahel region of West and Central Africa. Usually the rainy season there lasts four or five months, typically between July and October.

In its most basic form, SMC involves the regular community-based administration of antimalarials to address populations during the peak malaria season. The objective is to maintain concentrations of those antimalarials in the bloodstream that’s high enough to prevent malaria infections. That’s another important aspect of SMC – it’s meant to prevent new infections from developing. It’s not meant to treat existing infections.

The World Health Organization recommends that SMC should be targeted at children under five years. As I said earlier, they are the most vulnerable to malaria. The medicines are distributed door to door by volunteer community distributors. That’s really to ensure that as many children as possible are reached by the SMC campaign. Each course of the SMC medicines gives protection for round about 28 days and then the protection decreases quite rapidly. That means we need to give those drugs on a monthly basis during the peak malaria season – so during the rainy season. Therefore, each annual round of SMC comprises four or five monthly SMC distribution cycles.

As I said earlier, the rainy season in the Sahel is between July and October, so right now the 2021 SMC campaign is in full swing and we don’t have data yet on the target population across all the countries in the Sahel that implement SMC, but we estimate that round about 40 million children across the Sahel will be reached by SMC this year.

There’s quite a lot of evidence of the effectiveness of SMC. It’s well documented in clinical trials. It’s been found to prevent up to 75% of all malaria cases in children under five. It’s also been documented that SMC can be delivered safely at scale and that SMC is a very cost effective intervention – one study found that the average cost is about 3.63 $ per child a year. I‘ve listed some of the key references here if you want to read up on the available evidence.[1]

Of course, the heart of the SMC intervention is the monthly distribution of the SMC drugs during the rainy season. However, to make that happen there are lots of other pieces that need to be in place so the campaigns go smoothly. SMC is really a year round activity.

That starts with the planning phase – during the planning phase we estimate the target population, we decide which resources are needed where and when. Then those resources need to be procured and they need to be transported to the right place at the right time in the right quantity. We also engage with communities to make sure that the population is well informed about the intervention and that they’re supportive. That includes things like meetings with community leaders, radio spots, etc.

As you can probably imagine, there’s a huge training component – hundreds of thousands of SMC implementers are involved in distributing SMC and they all need to be trained before the campaign. Then, during the campaign they’re supervised by health workers, usually based at health facilities. In general, health facilities play an important role in SMC. If a child is identified as having malaria at the time of SMC distribution, that child should not get the SMC drugs but they should get referred to the health facility, get tested there – and if the test is positive they should receive antimalarials as per the national treatment policy. Also, while SMC side effects are very rare, they do happen and you need to have a system in place to manage those side effects. We call that a pharmacovigilance system, which is also coordinated through the large network of health facilities that participates in the SMC campaigns.

Finally, we invest in monitoring and evaluating the SMC campaign. For example, we conduct regular household surveys to give us an accurate measure of SMC coverage among the target population. One important point is that SMC is implemented through countries’ existing health systems and at Malaria Consortium we see our role as providing technical and logistical support to ministries of health across all these various intervention components.

To give you a sense of the scale of our program this year, we are one of the leading implementers of SMC globally at Malaria Consortium. Together with our partners in each of these countries we’re aiming to reach just under 20 million children under five in Burkina Faso, in Chad, in Nigeria and in Togo this year. In other words, we’re expecting to support the distribution to round about 50% of all the children in this area that will receive SMC this year. In Nigeria alone, we’re targeting over 16 million children in 11 states.

To give you a sense of our funding – about 60% of the target population that we’re reaching this year will be supported by philanthropic donations and the remaining 40% come primarily from the Global Fund to fight AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. We also have a smaller grant from the Korean Development Agency that comes for about 1% of our overall funding.

The World Health Organization started recommending SMC back in 2012. The very rapid scale-up of SMC, from zero in 2012 to 40 million in 2021, is very often seen as a success story – one of the few success stories that we’ve had in the malaria world over the last ten years or so. Philanthropic donations have really played a crucial part in making that happen. We primarily received those donations because we’ve been recommended as a top charity by GiveWell, which is an American organization that is very well respected, especially in the Effective Altruism communities. I would imagine most of the people on this call today would be familiar with GiveWell.

For Malaria consortium, what this funding does is that it gives us an enormous amount of planning security and of operational flexibility. I’ll just give you one recent example. A few months ago we were approached by the national malaria program in Nigeria about a funding gap that had emerged just before the start of this year’s SMC campaign in one of the states there, Borno. That gap meant that on very short notice about 2 million children were at risk of not being protected through SMC this year. Because of our experience and our relationship with the national malaria program, but most importantly – because of the fact that we can make very fast decisions about the use of the philanthropic funding for SMC without too much red tape – we were able to commit at very short notice to support SMC in Borno this year. Right now SMC is happening across Nigeria, including Borno, and that means that because of this flexibility we were able to make sure that two million additional children were protected with SMC this year.

Just a few final words on SMC outside of the Sahel. You may have wondered why I’ve only been talking about Sahelian countries so far. Surely there are other areas in Africa where malaria transmission is seasonal? Yes, there are. But currently, at least, the World Health Organization’s policy recommendation is to focus on Western Central Africa – the Sahel – because malaria transmission is seasonal there and there is little parasite resistance to the drugs that we’re using in SMC. However, we have now reached the stage where most – not all, but most – of the eligible children in the Sahel are being reached.

As I mentioned at the beginning of my talk, there’s recognition that we really need to optimize the tools that we already have at our disposal, like SMC. So the World Health Organization and others are now really pushing for SMC to be used more aggressively, including in geographies where there’s resistance to the drugs. I’m not going to go into any technical detail here, but there are good technical reasons to believe that SMC as a preventative intervention will still be effective in areas where resistance is high.

With that in mind, we have formed a partnership with the malaria programmes in Uganda and in Mozambique. We are conducting two research studies there to test the feasibility, the acceptability and the impact of SMC outside of the Sahel. In both countries, the protocols, the tools and the materials that we use in the Sahel where adopted to the local context and both projects are designed as two-year studies, with the first year looking more at feasibility and acceptability, then followed up in the second year by a much more robust trial of impact of effectiveness.

Right now we have results from the first year in Mozambique, where we implemented four cycles of SMC between November last year and February this year, because that’s the seasonality pattern in that part of the world – reaching about 70 000 children. We found that it’s very feasible, very acceptable. The coverage rates were round about the same as what we would see in the Sahel. The most interesting findings we have to date are from a non-randomized controlled trial where we followed up about 700 children in the two intervention districts and a third district that served as a control. We found that malaria had a protective effect of about 86%. The next phase of the study will be implemented later this year and we will be doing a proper randomized controlled trial as part of that. As I said, we have a very similar project in Uganda.

I think I need to stress that this is research and to date we only have a very limited set of data from the first project stage, so we shouldn’t get carried away. There are still a lot of questions that need to be answered about whether or not SMC will work in this part of the world. But if the results are positive – as we all hope and the signs are good, but we still need to confirm – then that would mean SMC could be used in a whole new geography across East and Southern Africa where malaria transmission is seasonal, so a lot more children could potentially benefit from SMC.

I hope this gives you a good overview of what SMC is and what Malaria Consortium does. I’ve listed a few reading materials that you might be interested in. One is our annual philanthropy report, which provides a lot of information about how we used the philanthropic funding for SMC last year[2]. The other’s a learning paper[3] where we reflect on the lessons from implementing SMC during the pandemic. I haven’t really talked about that much but I suppose you can imagine that maintaining mass distribution of a preventative malaria intervention during a pandemic requires a lot of adaptations and a lot of efforts, and this paper reflects on what we’ve learned from doing that. All our publications, of course, can be accessed on our website[4].

Finally, I just wanted to stress that while my role is about SMC (I work on SMC 100% of my time), Malaria Consortium – the organization I work for – has a lot of other projects and programs in Africa and Asia. Around our expertise of prevention, control and treatment of malaria and of other communicable diseases we have projects in a range of countries in Africa and Asia. If you want to find out more about our work you can always visit us on our website[5]. But for now, I’d like to say – thank you very much for your attention and I’m happy to answer any questions you may have. Thank you.

Zapraszamy również do przeczytania kolejnej części artykułu, w której poznacie odpowiedzi na wnikliwe pytania zadawane Christianowi przez uczestników webinaru.

– Redakcja EA Polska

bibliografia – publikacje cytowane w prezentacji Christiana:

[1] Meremikwu MM, Donegan S, Sinclair D, Esu E., Oringanje C. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in children living in areas with seasonal transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(2): CD003756.

ACCESS-SMC Partnership. Effectiveness of seasonal malaria chemoprevention at scale in west and central Africa: an observational study. Lancet. 2020; 396(10265): 1829-1840.

Gilmartin C., Nonvignon J, Cairns M, Milligan P, Bocoum F et al. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention in the Sahel subregion of Africa: a cost-effectiveness and cost-saving analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021; 9(2): e199-e208

[2] Malaria Consortium. Malaria Cosortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: philanthropy report 2020. London: Malaria Consortium; 2021.

[3] Malaria Consortium. Implementing mass campaigns during a pandemic: What we learnt from supporting seasonal malaria chemoprevention during COVID-19. London: Malaria Consortium; 2021